Congestion Pricing – An idea whose time has finally come (to the U.S.)

This post originally appeared on the EDR Group blog on April 10th, 2019. Thanks for colleagues proofreading help, etc.

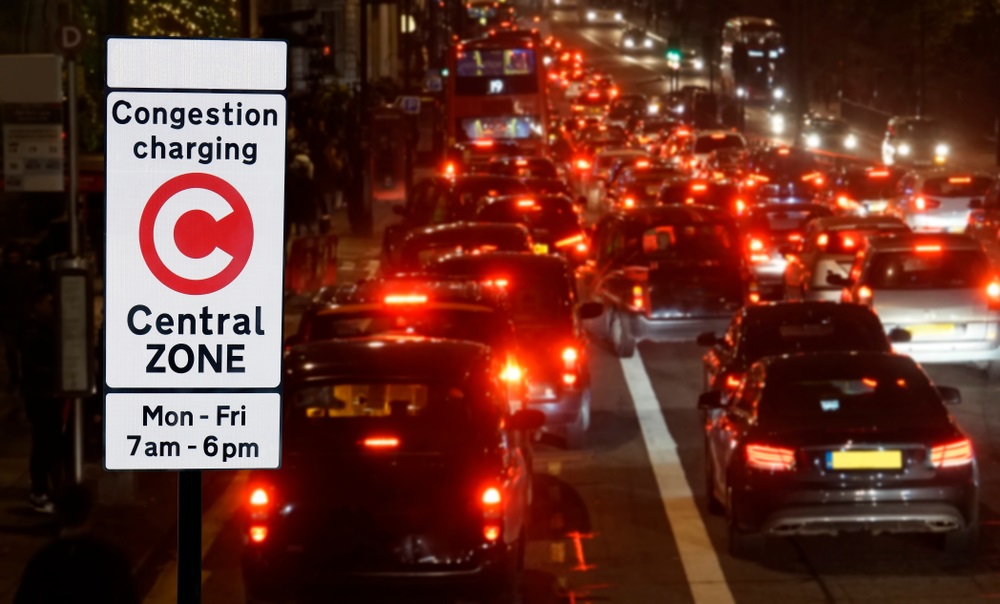

In the early hours of March 31st, New York State took the landmark step of moving forward with implementation of a congestion pricing policy for Manhattan. With this deal, NYC edges out other cities like Seattle and Los Angeles to be the first in the U.S. to impose a charge on all vehicles entering a specific zone of the city. Other kinds of congestion pricing like dynamic rates for express toll lanes have existed for years, but drivers generally have an alternative option to reach their destinations without paying a fee. Starting in 2021, that will not be the case for almost any vehicle traveling into Manhattan below 60th Street – only emergency vehicles and vehicles transporting someone with a disability are exempt from the charge established in New York’s legislation.

I wrote back in February about how congestion pricing and road usage charge discussions in the U.S. were beginning to get quite serious in response to a variety of factors, such as falling gas tax collections, new modes, and automated driving possibly being just around the corner. Just a month and a half later we see how suddenly these factors can come together for the policy environment to shift. It will be interesting to see if other cities, regions, and states quickly follow in New York’s footsteps and whether this is indicative of a shift in public acceptance of a congestion charge. One of the key sticking points for congestion charges is whether it is more or less equitable for certain groups of travelers, a debate that EDR Group is helping several states address through our studies of road usage charges.

The introduction of congestion pricing for all vehicles follows imposition of surcharges on for-hire ride services operating in the Manhattan core last spring. Under that policy, taxi users pay $2.50 per ride, travelers with providers like Uber and Lyft pay $2.75 per vehicle, and riders offering to share a trip pay $0.75 per traveler. NYC should be commended for making it cheaper for users to take a shared ride, although perhaps even greater discounts would be justifiable. Increasing ride-sharing might be one of the best ways to combat the additional vehicles on the road since new for-hire ride services started competing with traditional taxi cabs. Congestion charges of all types might also help encourage travel by transit, walking, and biking rather than automobile. EDR Group has ongoing work with FHWA to better understand just how effective these kind of price differentials are in encouraging travelers to share their rides instead of taking a private vehicle option. We are wrapping up survey analysis on how incentives affect the choices of different populations and beginning to apply these insights to testing various policy options.

The revenue gained from the congestion pricing policy is to be largely set aside to fund the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) capital backlog, as well as other regional transit and transportation priorities. Like many other metro areas whose transit systems were built-out relatively early in the 20th century, MTA customers are experiencing more and more transit service disruptions and seeking out for-hire ride services and other alternatives perceived to be more reliable. Congestion pricing revenues should allow MTA to raise almost $15 billion in bond funds to accelerate system modernization, avoiding some of the worst economic impacts of insufficient upkeep identified by EDR Group in last year’s APTA report. In the coming years and decades, New York’s first-in-the-nation congestion pricing experiment should provide key insights on whether and how user charges can become a mainstream element of transportation finance in the U.S.

2019-05-06 @ 17:36

To date, much of the academic literature has focused on theoretical models and simulation to demonstrate how rational firm behavior will changes as congestion adds to total transport cost. On the other hand, much of the industry writing has centered on stories about the many ways that businesses change behavior to avoid congestion impacts –by shifting operations, schedules and locations. This article seeks to span the two by providing a structural framework for classifying the different elements of supply chains and how congestion affects each of them. It then identifies the transportation performance measures and cost elements that need to be recognized in economic models of both firm behavior and broader economic development. An example is provided to show how more economic impact modeling can more realistically represent firm behavior and better inform public policy decision-making.